silvia

Joined: 10 Oct 2021

Posts: 268

Location: UK

|

Posted: Aug 26, 2025 14:29 Post subject: Spessartine Garnet and a farewell to Wu ‘Sham’ Posted: Aug 26, 2025 14:29 Post subject: Spessartine Garnet and a farewell to Wu ‘Sham’ |

|

|

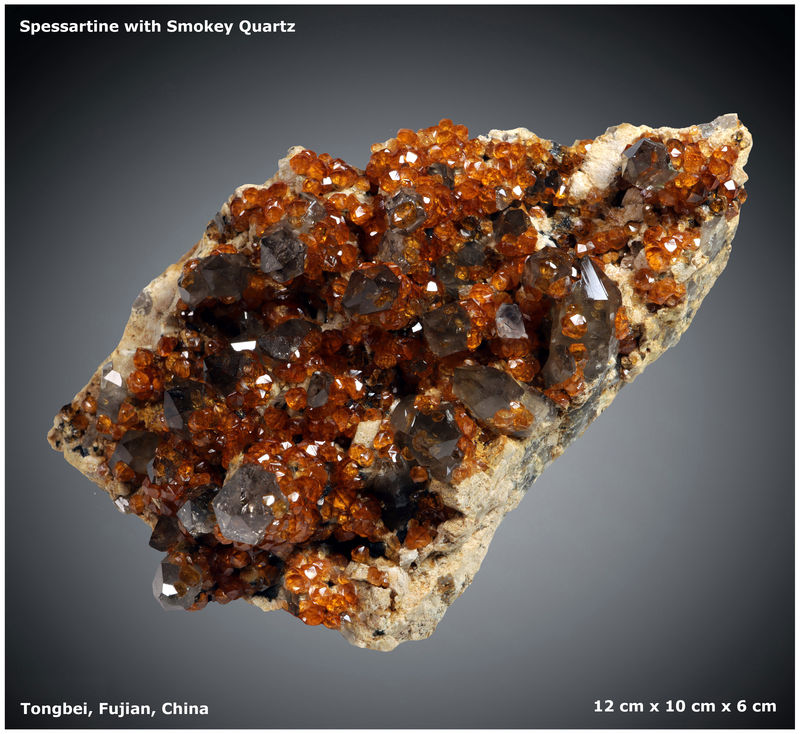

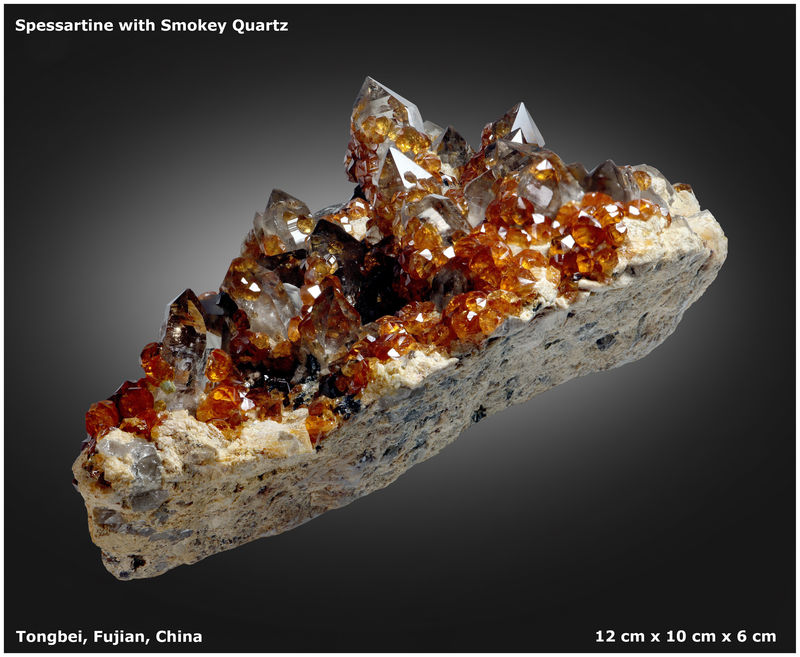

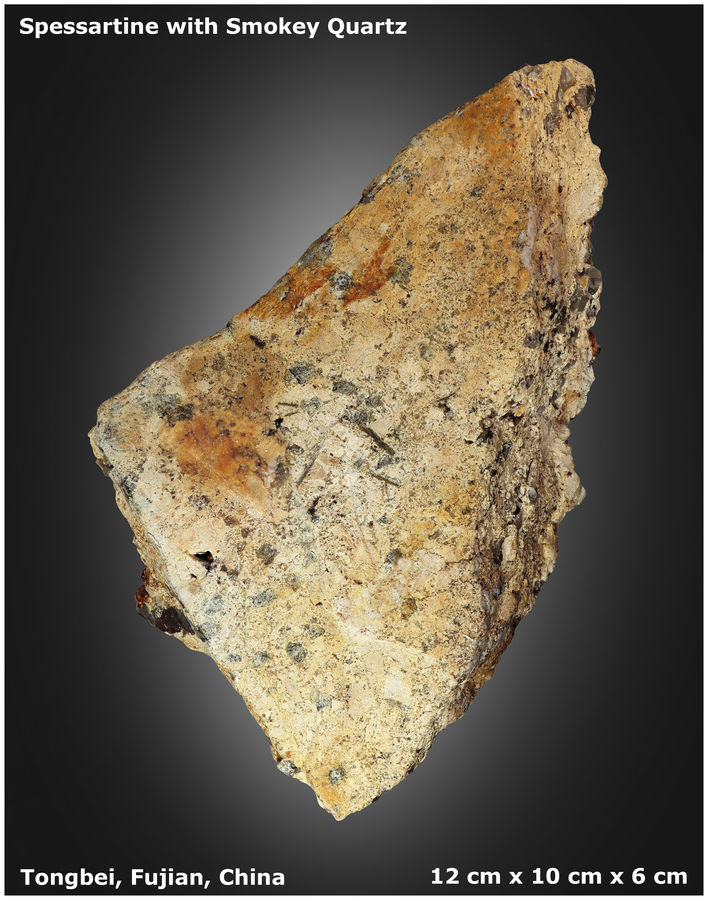

From southern Fujian Province in China, a region renowned more for its stunning landscapes and friendly locals than its mineral treasures, comes a classic combination of Spessartine Garnets and Smoky Quartz on Feldspar matrix. Spessartine from the Tongbei locality was a by-product of commercial granite mining — a contrast to traditional Chinese mineral operations — and was carefully extracted from miarolitic cavities in the granite.

What truly distinguishes these specimens is not only the intense orange hue of their Spessartine Garnet crystals but also their impeccable dodecahedral form. This particular cabinet-sized specimen offers a captivating melange of mineral delights. A dozen or so medium-sized Smoky Quartz crystals serve as the main backdrop, ranging in size from 1.5 cm to a respectable 4 cm, with the tallest strategically positioned towards the top of the specimen. The Quartz crystals exhibit a water clear clarity, seldom seen in most Smokey Quartz crystals, that beautifully contrasts with their fiery companions. Scattered gracefully around the bases of these Quartz crystals are oodles of bright orange-red Spessartine Garnets. These garnets, range in size from 1 to 4 mm and exhibit exceptional color, transparency and luster. Their exceptional shape and graceful dispersion across the matrix allow for each individual crystal to be fully appreciated, a striking contrast to the often-crowded formations typically found at this renowned locality. Nestled among the Spessartine Garnet crystals is a solitary, water-clear Fluorite crystal which adds another dimension of beauty and charm to the specimen.

Adding another layer of visual impact is the presence of the snow-white, Feldspar matrix which affords an aesthetically captivating back-drop to enhance the crystallographic features of both the Smokey Quartz crystals and the Spessartine Garnets. Overall, the specimen stands out as a handsome and vividly colored example of Fujian’s fine mineralogical legacy.

A brief note on photography

These photos were captured under simple lighting conditions using standard LCD globes. The camera used was a Canon EOS M6 Mark II, which employed a unique photo bracketing technique. Each photograph is a composite of about 400 individual shots, taken with the camera's manual settings. They were then processed using Canon’s Digital Photo Professional Software V20.10.0 and its Depth Composition function, followed post-processing using an old version of Photoshop.

The close-up shots were taken with an Andonstar ADSM302 Digital microscope. Its focus tube was manually adjusted to bring both the near and far fields into focus. These images are the result of approximately 20 individual shots, which were then processed using Helicon Focus V8.1.0, followed post-processing using an old version of Photoshop.

If there's enough interest in the photo bracketing technique and the practical use of digital microscopes in mineral photography, I would be happy to upload an extensive “how-to” article with pictures. I consider myself a novice collector and photographer, and this guide could help other beginners take some nice photographs. I am still learning!

| Mineral: | Spessartine and Smoky Quartz |

| Locality: | | Wushan Spessartine prospects, Tongbei, Yunxiao, Zhangzhou Prefecture, Fujian Province, China |  |

|

| Dimensions: | 12 cm x 10 cm x 6 cm |

| Description: |

|

| Viewed: |

43 Time(s) |

|

| Mineral: | Spessartine and Smoky Quartz |

| Locality: | | Wushan Spessartine prospects, Tongbei, Yunxiao, Zhangzhou Prefecture, Fujian Province, China |  |

|

| Dimensions: | 12 cm x 10 cm x 6 cm |

| Description: |

|

| Viewed: |

45 Time(s) |

|

| Mineral: | Spessartine and Smoky Quartz |

| Locality: | | Wushan Spessartine prospects, Tongbei, Yunxiao, Zhangzhou Prefecture, Fujian Province, China |  |

|

| Dimensions: | 12 cm x 10 cm x 6 cm |

| Description: |

|

| Viewed: |

43 Time(s) |

|

| Mineral: | Spessartine and Smoky Quartz |

| Locality: | | Wushan Spessartine prospects, Tongbei, Yunxiao, Zhangzhou Prefecture, Fujian Province, China |  |

|

| Dimensions: | 12 cm x 10 cm x 6 cm |

| Description: |

Each magnified photograph details the fine crystal formations of the specimen and has a field of view (FOV) of approximately 10 mm.

The top-right image displays Spessartine Garnets on Microcline Feldspar.

In the top-left, the Garnets are accompanied by a smoky Quartz crystal and a single Fluorite crystal.

The bottom-left photo reveals more Spessartine Garnets associated with Microcline Feldspar and Quartz.

The bottom-right image shows the matrix on the side of the specimen, corresponding to the view labeled “02 – SPESSARTINE.”

Wushan is a misnomer |

|

| Viewed: |

43 Time(s) |

|

| Mineral: | Spessartine and Smoky Quartz |

| Locality: | | Wushan Spessartine prospects, Tongbei, Yunxiao, Zhangzhou Prefecture, Fujian Province, China |  |

|

| Description: |

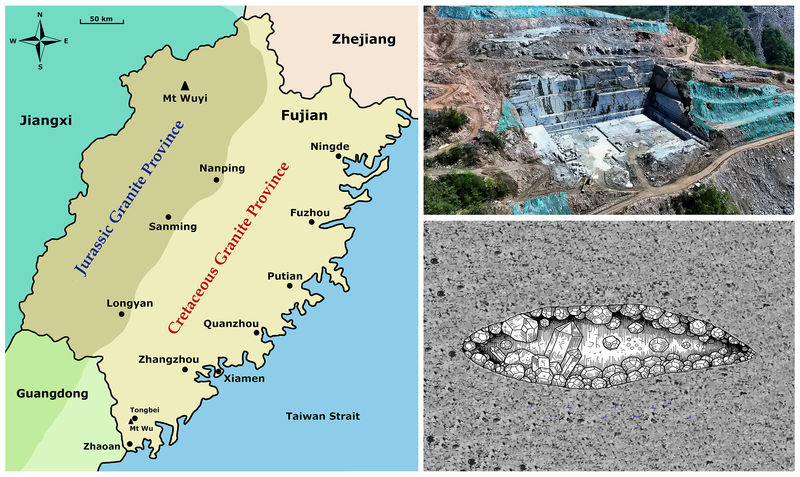

Photo 1 - Map, Quarry and Cavity

The diagram provides a geological overview of Fujian Province (Map by Silvia). In the upper-left, a map situates the province on China's southeastern coast and uses shading to delineate its two principal igneous zones: one Jurassic and the other Cretaceous in age. This broad classification reflects the dominant age of the granitic intrusions in each zone, not specific local geology. The upper-right features a photograph of a typical commercial Fujian granite quarry (Photo courtesy of Chao Li), below which is an illustration of a mineral-bearing miarolitic cavity (Diagram by Silvia).

Discussion

Spanning 800 kilometers along China's southeastern coast, the Cretaceous-age granitic belt in the provinces of Guangdong, Fujian, and Zhejiang is a world-renowned source of exceptional mineral specimens. This geological feature resulted from the Mesozoic-era subduction of the Paleo-Pacific plate beneath Eurasia, which generated vast quantities of magma that cooled slowly within the crust to form extensive granitic plutons.

Miarolitic Cavity Formation

A defining feature of this granitic province is the abundance of miarolitic cavities — crystal lined vugs that formed during the final stages of magma crystallization. As the silicate melt solidified, volatile components like water, fluorine, and boron, along with certain “incompatible” elements, become concentrated in the residual fluid. When the fluid reached saturation, a state often triggered by a decrease in lithostatic pressure from the overlying rock, it exsolved (separated) from the melt, creating open pockets within the largely solidified granite. This superheated, volatile-rich fluid provided an ideal medium for crystal growth. Its low viscosity and high ionic mobility facilitated the efficient transport of chemical constituents to nucleation sites, allowing for the formation of large and perfectly formed (euhedral) crystals.

Geochemistry and Spessartine Genesis

Miarolitic cavities are of significant petrological interest because they concentrate elements that are incompatible with the crystal lattices of common rock-forming minerals like Quartz and Feldspar. Elements such as Manganese (Mn), Beryllium (Be), and Lithium (Li) are preferentially partitioned into the final magmatic-hydrothermal fluid.

The formation of the region's famous Spessartine Garnets is a direct result of this process. The parental magma was inherently rich in Manganese, likely derived from the partial melting of Manganese-bearing meta-sedimentary rocks. As an incompatible element, Mn was concentrated in the fluid that filled the miarolitic cavities. Within this stable environment, slow cooling allowed the fluid to become supersaturated, leading to the methodical precipitation of gem-quality Spessartine crystals.

Mineral Assemblages and Characteristics

The Spessartine specimens from this belt, particularly those from Fujian province, are celebrated for their vibrant “Fanta” orange color, exceptional transparency, and razor-sharp crystal forms. A third of the significant mineral localities in the belt are famous for producing these garnets.

These brilliant orange crystals are often found in magnificent assemblages, perched aesthetically on a matrix of milky or smoky Quartz. They are frequently accompanied by lustrous blades of Feldspar (typically Microcline) and occasionally Schorl tourmaline or Topaz. This specific mineral association, such as Spessartine with smoky Quartz found in Fujian’s granite plutons, provides geologists with a direct sample of the late-stage fluid, indicating conditions of high Manganese and silica concentration and relatively high oxygen fugacity. |

|

| Viewed: |

43 Time(s) |

|

| Mineral: | Spessartine and Smoky Quartz |

| Locality: | | Wushan Spessartine prospects, Tongbei, Yunxiao, Zhangzhou Prefecture, Fujian Province, China |  |

|

| Description: |

Photo 2 – Wu Shan Mountain and Tourist Attraction site

Shown clearly in the aerial photograph is the Wu Shan Mountain, an extensive granite pluton located approximately 1.8 kilometers southwest of Tongbei. It is a site of significant geological interest. The photograph reveals the scope of the pluton, with prominent tourist features such as a scenic walkway and the main entrance — shown in the accompanying photos and clearly discernible in the aerial photograph (Tourist photos courtesy of Chao Li).

The locality is widely known in the mineral trade as the “Wushan Spessartine Mine.” This name, however, is a misnomer. There has never been a formal mining operation dedicated to extracting mineral specimens. Instead, the region's remarkable mineral wealth, particularly its world-class spessartine Garnet and smoky Quartz crystals, was uncovered as a byproduct of commercial quarrying for granite building materials.

A tension between economic activity and natural preservation has redefined access to Wu Shan's resources. The area has been designated a protected national park, and as a result, the collection of mineral specimens is now illegal. Although commercial granite quarrying is still allowed in designated areas, mineral collecting is now forbidden throughout the park.

This shift has significantly increased the value and historical importance of specimens already in circulation. It also poses a challenge for researchers and collectors, who must now study a famed locality through its legacy collections, documenting minerals from a source that, as a “mine” never formally existed and from an area no longer accessible to mineral collectors.

Wu Shan’s distinct mineralogy is directly linked to its geological origin. The pluton's formation is a result of tectonic activity during the Mesozoic Era, specifically the subduction of the Paleo-Pacific Plate beneath the Eurasian continental plate. This process led to the generation and intrusion of large bodies of granitic magma, of which the Wu Shan pluton is a prime example.

The exceptional, well-formed crystals found in the surrounding area are attributed to the presence of late-stage, volatile-rich fluids within the cooling magma. These hydrothermal fluids concentrated incompatible elements and created miarolitic cavities — pockets or voids within the granite — that provided the open space necessary for exceptional, gem-quality crystal growth. |

|

| Viewed: |

44 Time(s) |

|

| Mineral: | Spessartine and Smoky Quartz |

| Locality: | | Wushan Spessartine prospects, Tongbei, Yunxiao, Zhangzhou Prefecture, Fujian Province, China |  |

|

| Description: |

Photo 3 – Tongbei Village and surrounding area.

A Case Study: The “Wushan Spessartine Mine”

The “Wushan Spessartine Mine” in Fujian, China, serves as a classic case study in fabricated mineral localities. Famed for producing exceptionally vibrant, “Fanta orange” Spessartine Garnets, this supposed mine never actually existed. It's a clever marketing name invented by some dealers to give their specimens a more exclusive and traceable-sounding origin. This practice, however, highlights a significant and persistent problem within the mineral trade.

Adding to the confusion, numerous mountains in China share the name Wushan or a similar variant, such as Wuyishan. A particularly notable example is a region about 290 kilometers northwest of Tongbei, on the border with the neighboring province of Jiangxi, renowned for its fine teas and granite outcrops (see map). This specific location has also been erroneously cited by some vendors as the source of the Spessartine Garnet specimens.

Pinpointing the True Source: The Tongbei Area

This aerial photograph shows the region surrounding the former site of the so-called Tongbei Village. The landscape is now dotted with the remnants of various abandoned granite quarries, derelict dwellings, evidence of past farming, and several man-made lakes.

It is difficult to pinpoint the precise origin of the “Wu Shan” Spessartine specimens because the region contains numerous large granite outcrops and many abandoned quarries. A site known as Tongbei village is situated approximately 300 meters west of a major quarry, formerly a primary source for construction granite. Based on aerial photography and limited online information, it is unclear whether Tongbei was a traditional village or a support settlement built for the quarry. However, its immediate proximity to the quarrying operations strongly suggests it was the latter.

It is also noteworthy that the site, which appeared as “Tongbei Village” (GPS: 23.930744 Lat, 117.192602 Lon) on several versions of Google Earth over the past fifteen years, no longer exists. Recent aerial photographs (ca. 2025) from both commercial and military sources show that all surface structures have been removed and the area has been completely rehabilitated. Most of the other quarries in the area have also been rehabilitated. Kengzaiwei, the largest nearby settlement, is situated approximately one kilometre northwest of the main quarry and 500 metres north of the former site of Tongbei village.

Approximately 1.8 kilometers west of the Tongbei mining area lies the summit of Wu Shan Mountain. As the region's highest point, it serves as a notable local tourist attraction. It's highly probable that the Spessartine specimens recovered from this region get their common name from this mountain.

The only conclusion supported by this analysis is that the “Wushan Spessartine Mine” is a fiction. The true source of the specimens is almost certainly local quarries and outcrops near the former Tongbei settlement.

The Power of a Name: Marketing and Provenance

In the vibrant world of mineral collecting, a compelling and specific name can greatly enhance a specimen's appeal. These unique names often highlight a mineral's special qualities, helping it stand out in the market. In some instances, a distinctive name may be used to protect a new or sensitive discovery, allowing a source to be managed carefully without being overwhelmed by competitors. While this marketing can add a layer of mystique that elevates a specimen's prestige, it's helpful for collectors to be aware of how these names are used.

For the collecting community, understanding a specimen's true origin is a deeply rewarding part of the hobby. Provenance — a specimen's documented history — adds to its story and is a cornerstone of a meaningful collection. For researchers, accurate location data is invaluable, as it contributes to our collective understanding of geology and mineralogy.

Ultimately, transparency and clear information build a stronger, more trusting community for everyone, from dealers to hobbyists. This encourages collectors to engage in the fun of discovery by asking questions and learning the story behind each piece. Being curious and informed is a wonderful way for anyone to build a collection with confidence and pride.

The Broader Challenge: Unraveling Chinese Localities

Accurately determining the provenance of mineral specimens from China poses a significant and ongoing challenge. A confluence of linguistic barriers, inconsistencies in transliterating names to the Roman alphabet, and evolving administrative regions creates persistent difficulties for both researchers and collectors.

A primary source of confusion is China's linguistic diversity. Alongside the official national language of Mandarin (Putonghua), numerous regions have distinct local tongues like Cantonese, Hokkien, and Hakka. Consequently, a single place can possess multiple names. For example, the city known today by its Mandarin name, Xiamen, was historically called Amoy, a name derived from its pronunciation in the local Hokkien dialect. This issue is compounded by a history of inconsistent romanization. Before Hanyu Pinyin became the international standard, various other systems were common, including Wade-Giles (e.g., Pei-ching) and Chinese postal romanization (e.g., Peking). These older, often conflicting spellings persist in historical documents, creating multiple Western identities for what is now known as Beijing and obscuring a location's modern identity.

China's dynamic administrative geography adds another layer of complexity. Provincial, prefectural, and county boundaries have been redrawn countless times throughout history. A village that was once part of a specific county may now belong to a different one or may have been absorbed into a sprawling urban district with a new name. This makes reconciling historical records with modern maps incredibly difficult, especially when a record refers to a prefecture that no longer exists as a political entity.

Furthermore, the Chinese cultural concept of a “hometown” (jíguàn) often refers to an ancestral clan's place of origin, not one's actual birthplace. An individual might identify with a small, ancient village their family left generations ago, a place that can be nearly impossible to locate on a contemporary map. These overlapping historical, cultural, and administrative layers make pinpointing a specific Chinese locality a significant puzzle for mineral collectors and historians. |

|

| Viewed: |

42 Time(s) |

|

|

|