| View previous topic :: View next topic |

| Author |

Message |

Craig Hagstrom

Joined: 10 Jan 2025

Posts: 36

|

Posted: Jan 11, 2025 11:01 Post subject: Libyan Desert Glass Structure Posted: Jan 11, 2025 11:01 Post subject: Libyan Desert Glass Structure |

|

|

Libyan Desert Glass is often said to have no crystals, but it actually has many. Samples frequently have what appear to be threadlike crystals revealed through weathering. For any one piece these are virtually all parallel, and they follow what looks like the ground contour. As optical unconformities these are dismissed as impact products, but I disagree.

I suspect these crystals result from sand grains being laid down in strings when dunes are built. The strings are a result of static electricity influencing grain alignment as they fall to the ground. This must be common behavior of blowing sand, and LDG happens to make it visible. When the dune surface is melted by a quick heating event, these strings remain undisturbed and the individual grain lattices join to make long crystals.

There is no reference to this phenomenon in any LDG reports I've found, but there are surely many reports not available to me. I'm hoping that my writeup will intrigue people who have research links, or the technical background to evaluate my model. As a retired computer geek, I'm totally out of my depth. I just happened to run across this and as my wife will tell you I spend too much time thinking.

I've written out my conjecture, and then examined five LDG specimens to show how the model fits individual cases. I also list several tests that could be done (by people with more equipment than I have) to give evidence for or against my model.

Two of my pieces show what appear to be plant seeds surviving with their shape intact, although instantly reduced to a cinder, and of course now long gone. This makes it less likely that LDG was formed during a meteorite impact or air burst, either of which could generate forces 10,000 times greater than it takes to crush a seed. This supports the thesis that LDG was formed in an electrical event.

If this interests you, my writeup can be downloaded from archive-dot-org and is titled Libyan Desert Glass Structure. It's a 13M PDF. You can also find it by my name as author, along with some of my other stuff, but that gets you dangerously close to the rabbit hole.

If you think I'm crazy feel free to say so, I get this a lot. If there's a better explanation for what I'm seeing, please advise. If this has been common knowledge for the last century, let me know, give me a link, I've been the last one before. If you're a geologist who knows sand dunes, speak up. If you have the physics background to crunch the numbers, share your results. All feedback welcome.

|

|

| Back to top |

|

|

Roger Warin

Joined: 23 Jan 2013

Posts: 1250

|

Posted: Jan 11, 2025 14:58 Post subject: Re: Libyan Desert Glass Structure Posted: Jan 11, 2025 14:58 Post subject: Re: Libyan Desert Glass Structure |

|

|

There is no poetry in LDG.

It is a silica glass with 98% SiO2.

Of course, since this siliceous phase was extracted from sandstones by very hot water from a comet falling about 28 million years ago, there are also micromineralized black areas also containing iridium and black streaks illustrating the viscosity of this molten glass and even SiO2 crystals in high temperature phases such as cristobalite.

| Mineral: | Cristobalite |

| Description: |

|

| Viewed: |

11595 Time(s) |

|

| Mineral: | Libyan desert glass |

| Description: |

|

| Viewed: |

11578 Time(s) |

|

|

|

| Back to top |

|

|

alfredo

Site Admin

Joined: 30 Jan 2008

Posts: 1018

|

|

| Back to top |

|

|

Craig Hagstrom

Joined: 10 Jan 2025

Posts: 36

|

Posted: Jan 11, 2025 20:02 Post subject: Re: Libyan Desert Glass Structure Posted: Jan 11, 2025 20:02 Post subject: Re: Libyan Desert Glass Structure |

|

|

| Quote: | | Observing a thin section with transmitted polarized light under a petrographic microscope will quickly indicate whether there are long chains of crystals present or whether it's mostly just glass, as glass and crystals look very different through a petrographic scope. |

Thanks.

I was confident there were tools that would do this. As I mention in my writeup, I don't have them, so I'm flying blind. The question then is whether anyone has actually done this for LDG. If apparent crystals are covering the surfaces where flat, and appear to be coming out of the surfaces where oblique, is anyone confident that they don't continue inside?

The point of my document is not how LDG formed, but that it might give a window to how sand dunes form, if my conjecture about how charged grains interact is valid.

|

|

| Back to top |

|

|

Peter Lemkin

Joined: 18 Nov 2016

Posts: 403

Location: Prague

|

Posted: Jan 12, 2025 07:54 Post subject: Re: Libyan Desert Glass Structure Posted: Jan 12, 2025 07:54 Post subject: Re: Libyan Desert Glass Structure |

|

|

Nowhere do you indicate or hint why you or anyone would be led to think there are "hidden" small linear crystals. LDG is a glass. Glasses don't have crystals by definition. It is fairly well established that the SDG [mostly found in Egypt, so badly named] was formed by one or multiple meteor impacts. Impact glass from meteors is well known [moldavites and the large dark ones from SEA just two examples]. The impact crater for moldavites found in the Czech Republic has been established to be Reis Crater in Germany. Finding craters under the Sahara is not easy for obvious reasons, but I believe radar has located some not far from much of the LDG. You seem [IMHO] to find 'theories' in search of evidence; answers in search of a question, rather than evidence needing theories. I have many pieces of LDG, moldavites and SEA tektites and none have surface or other features that would lead me to head in the directions you have. You have already hinted this is how your mind usually works, and your other papers/posts are 'rabbit holes' dug away from standard scientific theories. Anyway, with the right equipment this can be settled and I fear it will not support you. Lighting strikes form fulgerites not desert glass and tektites. How dunes form the way they do, move and form the patterns they do, even why N. Africa has so much sand is well established. Not that a scientific theory or consensus can't be wrong, but it usually takes some evidence that doesn't fit to start looking for a new theory. .

Kebira Crater Mystery in Sahara Desert

Fig. 1 Sahara Desert near the Border of Libya and Egypt

Large topographic structures on the Earth may escape recognition from the ground but are sometimes spotted in satellite images. Many meteorite impact craters might be typical of such cases. Researchers from Boston University recently found a large circular topographic structure in the desert area on the border of Libya and Egypt while investigating satellite images. Figure 1 is a reprint of the C region image from this " Seen from Earth; Circular Farms and Impact Craters in the Sahara" issued on November 12, 2004, which clearly captures this circular structure in the upper right. It has bold features, but no one noticed it until recently.

Fig. 2 Topographic Structure named Kebira Crater

Kebira Crater (kmz, 4.36MB, Low Resolution) as seen on Google Earth

Figure 2 is a close-up of this structure as observed by Daichi in July 2007. Although water and wind erosion marred the shape of the structure, a whitish circular sandy area surrounding the dark-brown central uplift can be recognized. A partially remaining outer rim (indicated by red circle) surrounds it. The outer rim was almost obscured by wadi and wind erosion but retains its overall circular pattern. The central uplift is also generally ring-shaped. The double-ringed structure bears the impression of a meteorite impact similar to structures frequently seen on the Moon and Mars. The outer rim is approximately 31km in diameter, which is about twice the size of the Sahara's current largest Oasis Crater in Libya (18km in diameter; also visible in Fig. 1), and more than 25 times the size of Arizona's famous Barringer Meteor Crater. Researchers from Boston University suspected that this might be a newly found meteorite impact crater and announced their discovery on March 3, 2006. The crater was named Kebira, meaning "large" in Arabic. The news of this discovery circled the world at that time. The intruder (meteorite or comet) is estimated to have been about 1.2km in diameter, and the energy released was equivalent to a nuclear explosion of more than 100,000 megatons. The impact would have wreaked devastation for hundreds of kilometers. The date of the impact is not known exactly, but the geological features of this area indicate that it may have been formed tens of millions of years ago.*1

Researchers from Boston University were, in fact, examining satellite images and looking for meteorite impacts , which may have created the mysterious glass fragments known as the Libyan Desert Glass (LDG). LDGs are yellow-green glass chunks, sometimes as large as a football, which were found on the desert surface between the giant dunes in southwestern Egypt and Libya. Since their discovery in 1932, their origin has long been a mystery. The famous Tutankhamun's Pectoral found in his anthropoid is decorated with an LDG scarab (an icon of a beetle that ancient Egyptians carried as an amulet). LDG is an amorphous glass of silicon dioxide (SiO2) with 98% purity, which can be heated up to 1,700°C before it begins to melt. The composition and structure of LDG is consistent with the scenario that it was formed from melted sand including silica, and then cooled slowly in the atmosphere.

Some samples are rich in iridium,*2 which is very rare on Earth but is typical of extra-terrestrial bodies such as meteorites or comets. All these characteristics of LDG indicate a meteor impact origin whose enormous heat melted sand and mixed iridium. However, there was no known impact site in the immediate area in which the LDG could have been created. Kebira Crater may be an important candidate for solving this mystery.

https://www.eorc.jaxa.jp/en/earthview/2008/tp080109.html

(link normalized by FMF)

| Craig Hagstrom wrote: | | Quote: | | Observing a thin section with transmitted polarized light under a petrographic microscope will quickly indicate whether there are long chains of crystals present or whether it's mostly just glass, as glass and crystals look very different through a petrographic scope. |

Thanks.

I was confident there were tools that would do this. As I mention in my writeup, I don't have them, so I'm flying blind. The question then is whether anyone has actually done this for LDG. If apparent crystals are covering the surfaces where flat, and appear to be coming out of the surfaces where oblique, is anyone confident that they don't continue inside?

The point of my document is not how LDG formed, but that it might give a window to how sand dunes form, if my conjecture about how charged grains interact is valid. |

|

|

| Back to top |

|

|

Craig Hagstrom

Joined: 10 Jan 2025

Posts: 36

|

Posted: Jan 12, 2025 11:09 Post subject: Re: Libyan Desert Glass Structure Posted: Jan 12, 2025 11:09 Post subject: Re: Libyan Desert Glass Structure |

|

|

| Peter Lemkin wrote: | | Nowhere do you indicate or hint why you or anyone would be led to think there are "hidden" small linear crystals. LDG is a glass. Glasses don't have crystals by definition. |

I indicate it in my document which is available on archive-dot-org, as I mentioned in my first post. I understood that LDG was a glass, which is why I was astonished to find all these striations that look like crystals at the scale of sand grains. If there's another way to describe them that doesn't involve crystals, I'm certainly ready to hear it. This isn't my field. But they look like thready crystals being revealed by etching/weathering.

They lie on surfaces that appear to have been parallel to the dune surface, and they cut right through surfaces that appear to have been oblique to the dune surface. They make a parallel bundle for each sample, with a few outliers. They don't accrete on the surface of samples. And if I'm finding them, others must have seen them. I presumed that geologists have optical tools, as was pointed out above, that could look at a slice of the stuff and see them all shot through with crystals, if they're crystals. I don't have that gear.

None of the LDG reports I found online talk about surface features much. They discuss high pressure chemistry, gross mixing of minerals, but nothing about these strange striations. So I thought it over and came up with a couple hypothetical ways they might be created, and compared five of my samples to my hypotheses. The hypotheses don't seem to conflict with what I see.

So I wrote it up, put it online, and came here for input. Y'all do this stuff for a living, and I'm just a retired computer geek.

If you haven't read my document, it isn't quite fair to say "nowhere do I indicate...", because that's where I lay out what I have.

In the course of my exploration I found two pieces that have what appear to be casts of some kind of plant seed. They might be some other kind of embedded object, and if anyone has an idea I'm all ears. But there are about a dozen in two of my samples, and seven of those are well enough enclosed to make a good case that a real object was embedded there. They would have been reduced to a cinder of course, and nothing's there now but the cast. But I don't know how to square them with the high-pressure chemistry of an impact that the reports cite. I don't know how an impact can melt sand to glass by pressure and yet not crack a pecan, as it were.

The creation event really isn't my main interest, as I say in my OP above, as I say at the start of my document. The creation event thought was sparked by the ongoing pole excursion, and led me to look at LDG, but once I found the apparent crystals they became what I wanted to figure out. So I'm willing to discard formative event evidence and debate entirely.

|

|

| Back to top |

|

|

Craig Hagstrom

Joined: 10 Jan 2025

Posts: 36

|

Posted: Jan 12, 2025 13:10 Post subject: Re: Libyan Desert Glass Structure Posted: Jan 12, 2025 13:10 Post subject: Re: Libyan Desert Glass Structure |

|

|

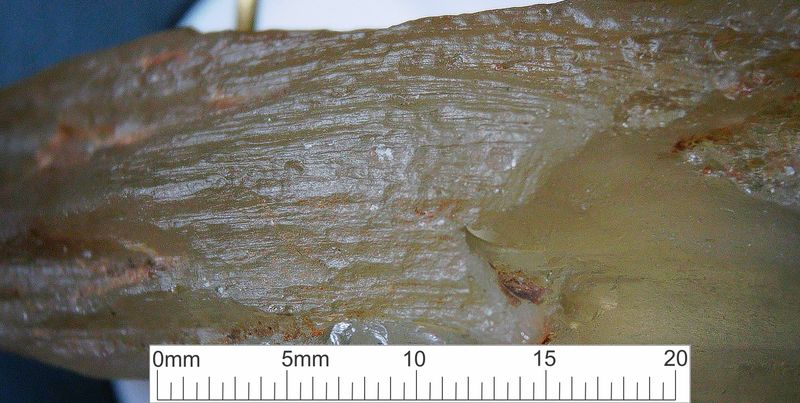

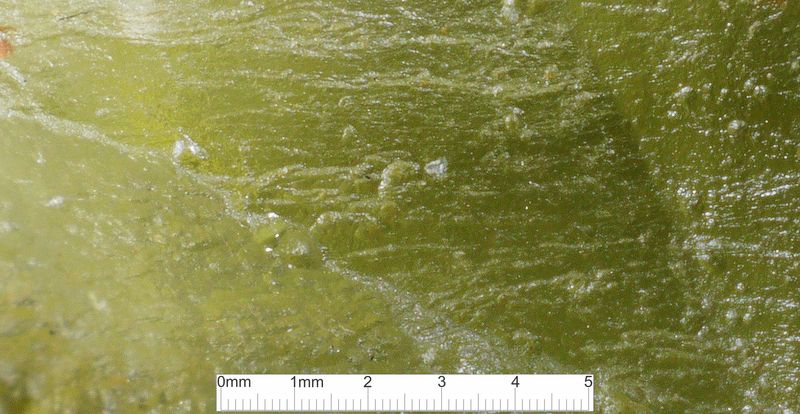

Here's a couple samples. I don't know what these lines mean. My conjecture is that they're crystals formed from threads of sand grains as laid down. The first is a closeup about 8 mm wide, showing the thread-like sort of woven striations. The second is about 9 cm wide. Notice the curved striations at the top left, as if it's tracing the top surface of a sand ripple.

I don't know how prevalent this is. Maybe it's rare. They won't show on a piece that's been recently abraded by wind, I suppose, or tumbled in a wadi. Maybe most LDG has no crystals at all, having been heated too much for any seed crystal to have survived. But they aren't hard to find if you're looking for them.

If one is sliced and examined and has no external striations, I don't know the odds of finding anything interesting inside. I wouldn't even try it unless there are external signs.

I'm not asserting that all LDG is shot through with crystals. I'm saying that where LDG is shot through with what looks like crystals, it calls for an explanation.

| Locality: | | Wadi Natrun depression, Valley of the Natron Lakes, Western Desert, Egypt |  |

|

| Dimensions: | about 8mm field of view |

| Description: |

|

| Viewed: |

11334 Time(s) |

|

| Locality: | | Wadi Natrun depression, Valley of the Natron Lakes, Western Desert, Egypt |  |

|

| Dimensions: | about 9cm side to side |

| Description: |

|

| Viewed: |

11325 Time(s) |

|

|

|

| Back to top |

|

|

Roger Warin

Joined: 23 Jan 2013

Posts: 1250

|

Posted: Jan 13, 2025 01:10 Post subject: Re: Libyan Desert Glass Structure Posted: Jan 13, 2025 01:10 Post subject: Re: Libyan Desert Glass Structure |

|

|

| I am collecting my photos for this description of the LDG.

|

|

| Back to top |

|

|

marco campos-venuti

Joined: 09 Apr 2014

Posts: 240

Location: Sevilla

|

Posted: Jan 13, 2025 08:16 Post subject: Re: Libyan Desert Glass Structure Posted: Jan 13, 2025 08:16 Post subject: Re: Libyan Desert Glass Structure |

|

|

Hi Craig, I like that you think and observe a lot, but I have to say that you have taken a less than productive path. I would like to clarify some concepts about natural glasses that might be useful to you and to others.

In nature, glass is a rare occurrence. We only have obsidians and tektites. Other glasses form small masses, (not fecet grade). To understand tektites we must first understand obsidians.

Why does a rhyolitic lava sometimes form a rhyolitic rock and sometimes a completely glassy obsidian? In literature it is explained by rapid cooling, but this is false. What could cause one lava to cool more quickly than another? A lava contains phenocrysts (crystals formed in the magma) and microcrystalline groundmass (crystals formed after the lava has been emplaced during cooling). Obsidians are aphyric, they do not contain neither phenocrysts nor microcrystalline groundmass, therefore they are 100% glass.

Obsidian is created by a particular phenomenon whereby a silicate melt increases its glass transition temperature (Tg) as the water content in the glass decreases. This is the temperature at which lava solidifies and is an exact temperature. Most magmas solidify over a wide range of temperatures, while their crystalline components crystallize. Obsidians solidify completely at an exact moment.

A rhyolitic magma with abundant water in solution (+/-4-5%) has a low Tg, 300-400 C below the effusion temperature (+/-900 C). Therefore, after the eruption, it has time to crystallize during cooling and forms a partially crystallized rhyolitic rock. If it has a lot of time in subvolcanic conditions, a granite is formed. On the contrary, a rhyolitic lava with low water content (<1%) has a high Tg, a few degrees below the magma effusion temperature, so there is no time to crystallize and we will have an obsidian. For this reason the obsidian lava flows are deeply fractured. Some supposed obsidians called Pitchstone with high water content are actually welded tuffs.

But why does that lava have so little water? Rhyolitic lavas are formed by two phenomena, partial melting and fractional crystallization. The first process is the most important and involves a lowering of the melting temperature in the crust due to the presence of water and alkalis which are two fluxes. Since any rock in the crust is composed of many minerals, each of which has a distinct melting point, the first melt that is produced from the fusion is composed of the lowest temperature minerals, which are quartz and feldspar. So we have a partial melting of the rock that produces a magma of rhyolitic composition.

So water is present at the time of the formation of the magma and must have escaped from the melt in some way. Magmas that produce obsidian must therefore have been degassed, that is, they have lost water. To degas a magma it must have been overheated. This happens in certain geological contexts with asthenospheric rises for example after a caldera collapse. In practice there is a large cavity in the crust and the mantle much hotter than the crust rises increasing the temperature. Overheating also explains why obsidians are aphyric, that is, they don't even have phenocrysts.

During the overheating of the magma, gases and therefore water escape upwards and accumulate in the upper parts of the magma chamber. These gases will be responsible for an explosive eruption made of fragments of pumice, that is, a glass rich in gas bubbles. When the gases run out, the eruption becomes effusive and obsidian is poured out.

From all this we understand that obsidian can only form by creating a melt with a lot of water and then degassing it until there is very little.

In tektites we have even less water than in obsidians. Therefore, a fusion due to any process cannot explain its genesis. Fulgurites are rich in water (+/- 10%) in fact they form only if the rock on which the lightning strikes is rich in water. One case is the phenomenon of the Fulgurite of Torre de Moncorvo (Portugal) which was created by the impact of lightning on a high voltage pole. It is an anomalous case and forms a massive glass similar to obsidian but with abundant crystalline residues.

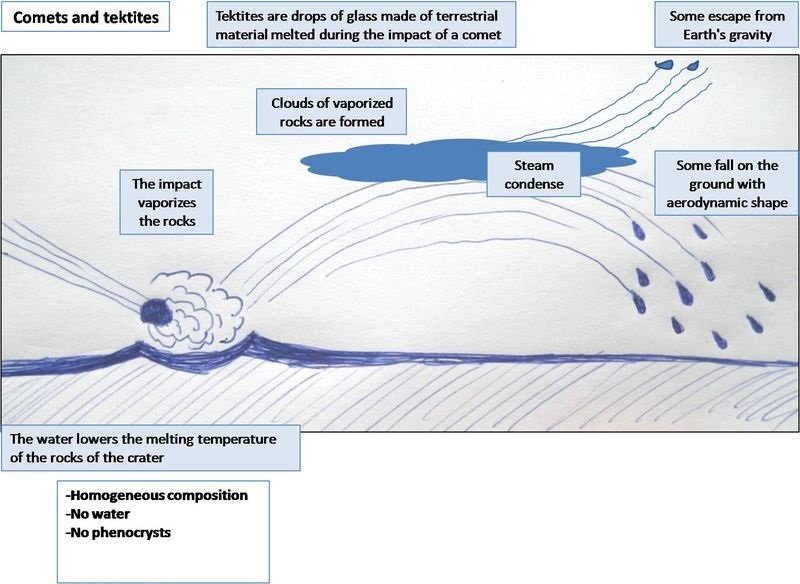

How does the glass of tektites degas? The hypothesized process is that of sublimation. Tektites are formed when a comet falls on Earth. Today we know that they are comets, I believe because of the oxygen isotopes. A meteorite does not create tektites, at most some impact glass, that is, glasses that form on the bottom of the crater at high pressures and temperatures (with HPHT minerals), but they are dirty glasses. Comets are made of ice and therefore transport the flux. Terrestrial rocks are sublimated and in this process they degas completely. In practice we have a partial melting of the low temperature component. A rain of glass then creates the tektite field. Since the sublimated glass has very little water, its Tg is very high and therefore the tektites do not remain molten for a long time, solidifying quickly. However, some fragments form so high that they re-melt during re-entry into the atmosphere creating fluidal structures on the surface, like in meteorites. Sublimation is a process at very high temperatures, but at atmospheric pressure.

Most of the structures we see in tektite fragments are produced after the fall. Glass is easily attacked by basic water through a reaction called Alkali Silica Reaction (ASR) that occurs at pH>9. ASR creates pitting, that is, small spherulites form inside the glass in which the glass is dissolved. The water molecule is small enough to slowly pass through the glass. When it encounters an air bubble, ASR begins and dissolves the glass. The result of ASR is a gel of silica and alkali polymers. The polymer molecules are too large to escape from the bubble and therefore generally recrystallize inside, long time later. In some cases, however, this gel can escape and we found empty spherulites.

The result of pitting is therefore different if it is on the surface of the fragment or inside it. On the surface, a small spherical cavity forms whose content has been carried away. Inside it, a spherulite forms. Spherulites are common in obsidians, LDG and even in the medieval stained glass windows of many important cathedrals.

It is generally said that spherulites in glass are made of cristobalite. However, cristobalite is a very high temperature mineral (1470C), totally incompatible with a rhyolitic magma. Furthermore, the high Tg prevents any crystallization in glass, both in obsidians and in tektites which in fact are both aphyric. The result of ASR is silica gel or in other words opal. We know that opal has diffraction peaks similar to those of cristobalite, in fact it is also called CT-opal, that is cristobalite-tridymite-opal. So the supposed cristobalite is nothing more than opal derived from the solidification of the residues of ASR inside the spherulite. The composition of spherulites is microcrystalline and generally consists of various associated minerals, so it could not be the result of crystallization in a magma. In alkaline lavas, we have fibrous spherulites with a feldspar component.

From a genetic point of view, the LDG is undoubtedly a tektite, but it is a bit anomalous compared to other tektites. It has a bit more water, forms angular blocks and of much larger dimensions. I do not know of models on the explosion that would have produced the tektites, but I suppose that some variables such as the height and angle of the explosion could condition the type of sublimation. I would dare to suppose that a part of the LDG was formed very close to the ground in very large blocks that were then fragmented again.

I hope that some of these ideas can help the discussion on a topic that has always fascinated many people, but on which there is a lot of confusion in the literature.

So finally:

LDG has no crystals, those lines you see are chemical erosion grooves.

You can't inherit elements from the ground because the glass was completely melted.

The term "Libyan Desert Glass" refers to a geographical name, the "Libyan Desert" that was coined when modern Libya and Egypt didn't exist yet. Likewise Gulf of Mexico was coined when neither Mexico nor the United States were born (unfortunately I don't think Trump reads the FMF!).

| Description: |

| Diagram of the formation of tektites by sublimation of terrestrial rocks |

|

| Viewed: |

11187 Time(s) |

|

|

|

| Back to top |

|

|

Craig Hagstrom

Joined: 10 Jan 2025

Posts: 36

|

Posted: Jan 13, 2025 15:09 Post subject: Re: Libyan Desert Glass Structure Posted: Jan 13, 2025 15:09 Post subject: Re: Libyan Desert Glass Structure |

|

|

Marco, thank you for the thoughtful response.

Regarding the erosion grooves, I have no expertise in the area. But consider the image below with curved striations. This is a closeup of one I showed above. The sand appears to have been laid down in a curve, as if this is the top of a sand ripple. The grooving can be traced through some pits in the upper part of the shot, and they are continuous as they go into and come back out of the pits. It doesn't look like grooving, it looks like layers.

The other image is a knapped piece. There is a cusp left by the knapping, running from the lower right to the top right of center. The apparent crystals can be seen running from one side of the cusp to the other, but disappear in the cusp itself. In other words, the crystals are not a surface feature, but are intersected by the knapping. I interpret this to mean that the knapping exposed fresh surface, and chemical etching exposed the crystal structure.

| Locality: | | Wadi Natrun depression, Valley of the Natron Lakes, Western Desert, Egypt |  |

|

| Dimensions: | as in image |

| Description: |

|

| Viewed: |

11133 Time(s) |

|

| Locality: | | Wadi Natrun depression, Valley of the Natron Lakes, Western Desert, Egypt |  |

|

| Dimensions: | as in image |

| Description: |

|

| Viewed: |

11136 Time(s) |

|

|

|

| Back to top |

|

|

alfredo

Site Admin

Joined: 30 Jan 2008

Posts: 1018

|

Posted: Jan 13, 2025 15:39 Post subject: Re: Libyan Desert Glass Structure Posted: Jan 13, 2025 15:39 Post subject: Re: Libyan Desert Glass Structure |

|

|

| It's not really a crystal structure, just the way glass etches. If you take a piece of beer bottle glass - pure glass with no crystals in it - and drip diluted hydrofluoric acid (very dangerous!) over it, or ammonium bifluoride solution, the surface of the glass will slowly dissolve and leave etch patterns like this. I do not know why glass does this.

|

|

| Back to top |

|

|

Craig Hagstrom

Joined: 10 Jan 2025

Posts: 36

|

Posted: Jan 13, 2025 15:52 Post subject: Re: Libyan Desert Glass Structure Posted: Jan 13, 2025 15:52 Post subject: Re: Libyan Desert Glass Structure |

|

|

| alfredo wrote: | | It's not really a crystal structure, just the way glass etches. If you take a piece of beer bottle glass - pure glass with no crystals in it - and drip diluted hydrofluoric acid (very dangerous!) over it, or ammonium bifluoride solution, the surface of the glass will slowly dissolve and leave etch patterns like this. I do not know why glass does this. |

I've done some glass etching to make store signs, so I understand the process. In the case of LDG I have pieces that show this linear pattern on one side, which tells me the crystals (or whatever we want to label the features) are congruent with that surface. The other face has sloped sides, as in my knapped piece, and the features do not lie on the surface but appear to intersect it. In other words, there is some structure being exposed which is organized and has parallel parts, and is larger than the specimen.

But this is supposedly loose sand that was melted by some heat event. So the question is what is the organizing property or physical feature? What's going on in there that preceded the stone being melted, broken up and flaked off, which is now being exposed?

That's what led me to formulate two conjectures about the cryptic structure inside LDG, which I outline in my writeup. One gives layers like extremely thin varves, and one gives thready crystals. When I compare those models to my specimens, I see a little evidence of layers, as just above, but mostly threads.

|

|

| Back to top |

|

|

alfredo

Site Admin

Joined: 30 Jan 2008

Posts: 1018

|

Posted: Jan 13, 2025 16:19 Post subject: Re: Libyan Desert Glass Structure Posted: Jan 13, 2025 16:19 Post subject: Re: Libyan Desert Glass Structure |

|

|

Threads (or "worms" as the locals there call them) of lechatelierite (pure silica glass) embedded in moldavite glass is the feature used to distinguish moldavite tektites from fake ones made out of remelted green bottle glass. Supposedly these worms can't be faked, or at least not without a great deal of effort.

Some collectors think the lechatelierite "worms" are melted quartz grains that got elongated or twisted by turbulence inside the still molten moldavite glass. I haven't seen any studies of that however.

The lechatelierite is more resistant to erosion than regular glass, so one sometimes finds them standing out of the surface of moldavites.

|

|

| Back to top |

|

|

marco campos-venuti

Joined: 09 Apr 2014

Posts: 240

Location: Sevilla

|

Posted: Jan 14, 2025 09:51 Post subject: Re: Libyan Desert Glass Structure Posted: Jan 14, 2025 09:51 Post subject: Re: Libyan Desert Glass Structure |

|

|

Glass has curved flow lines within it that have slight chemical and color variations. Those are what you call crystals, but they are not. You cannot have remnants of sand structures after melting it. Assuming there were dunes in Egypt 28 My ago, which I doubt.

Worms are surface structures on which chemical dissolution is concentrated. They are produced by filamentous microbial colonies (bacteria and fungi) present within the soil that have the ability to create local variations in chemical conditions, especially pH. They are found not only on glass pebbles but also on many calcareous pebbles and are often concentrated only on the lower side of the pebble.

|

|

| Back to top |

|

|

Craig Hagstrom

Joined: 10 Jan 2025

Posts: 36

|

Posted: Jan 14, 2025 10:48 Post subject: Re: Libyan Desert Glass Structure Posted: Jan 14, 2025 10:48 Post subject: Re: Libyan Desert Glass Structure |

|

|

| marco campos-venuti wrote: | | Worms are surface structures on which chemical dissolution is concentrated. They are produced by filamentous microbial colonies (bacteria and fungi) present within the soil that have the ability to create local variations in chemical conditions, especially pH. They are found not only on glass pebbles but also on many calcareous pebbles and are often concentrated only on the lower side of the pebble. |

This is interesting. Can you point me to resources where I can find out more?

|

|

| Back to top |

|

|

|